Whisky is just beer without any hops, distilled and then matured in an oak cask.

This is a mantra almost every whisky fan has heard at least once in their lifetime. In fact, if you’ve gone to any number of public tastings you’ve probably heard it more times than you can remember… but it’s not true.

While it is a common adage, one created to make explaining production to whisky-virgins easier, it’s one promulgated by Scottish brand ambassadors and only fits in with the European definitions of whisky. There, the acceptable ingredients are limited to water, yeast, grain and wood. In America, we do whatever the hell we want, so long as we have enough money to shut up the naysayers. Sometimes, we don’t even age our stuff in casks. Now, we’re adding hops and we don’t even have to tell you that they’re in there. This is America! What now, bitch?!

While it is a common adage, one created to make explaining production to whisky-virgins easier, it’s one promulgated by Scottish brand ambassadors and only fits in with the European definitions of whisky. There, the acceptable ingredients are limited to water, yeast, grain and wood. In America, we do whatever the hell we want, so long as we have enough money to shut up the naysayers. Sometimes, we don’t even age our stuff in casks. Now, we’re adding hops and we don’t even have to tell you that they’re in there. This is America! What now, bitch?!

In France and many Germanic countries, spirit made from grain and hops goes by a few different names: eau de vie de bier, bierschnaps or grappa di bier, among others. Part of the distinction lies in the hops themselves, though the other part is commonly related to aging. Only a handful of eau de vie de bier brands choose to mature in casks, and often not long enough to qualify as whisky by the EU definition. Despite the word whisky‘s coincidental similarity to eau de vie (both share an etymology that trace back to the translation, water of life) these are technically different products. In the US, though, there are ways around the age issue, and putting hops in the mix isn’t always a deal-breaker either.

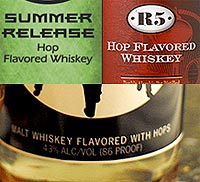

For a long time, I believed that if you added hops to a whisky’s mash bill, you had to add the phrase “hop-flavored” to the label. It was it’s own category. The main culprit behind that notion was Charbay, a distillery in California; the first to use the label “hop-flavored” on their whisky. They would and do tell people that they were the first to consider using bottle-ready brewer’s beer instead of the sour distiller’s beer commonly used in whisky, and that the TTB gave them a new category to be able to do it. Hops were forbidden, according to their narrative, just ignore their new Doubled and Twisted light whisky, which bears hops in the mash and a mysterious lack of the words flavored or hops on the label.

For a long time, I believed that if you added hops to a whisky’s mash bill, you had to add the phrase “hop-flavored” to the label. It was it’s own category. The main culprit behind that notion was Charbay, a distillery in California; the first to use the label “hop-flavored” on their whisky. They would and do tell people that they were the first to consider using bottle-ready brewer’s beer instead of the sour distiller’s beer commonly used in whisky, and that the TTB gave them a new category to be able to do it. Hops were forbidden, according to their narrative, just ignore their new Doubled and Twisted light whisky, which bears hops in the mash and a mysterious lack of the words flavored or hops on the label.

In hindsight, I feel extremely gullible. Charbay’s argument is very hard to swallow: distillation and brewing have been around for a very long time, so long that history surrounding it is lost or murky at best. Bierschnaps is not a new invention, either. The idea that nobody ever thought of distilling drinking beer and aging it in a cask is as ridiculous as the price of the first, two-year old Whisky Charbay sold. People have been brewing and filling their casks with anything and everything they could get their hands on since the very beginning. Also, there are documented examples of putting hops in American whisky mash going back as far the 1700’s.

Hop-flavored means that the whisky has, literally, been flavored, the way you flavor coffee with hazelnut creamer or mulled cider with a cinnamon stick. Every other artisan distiller making the flavored stuff has the integrity to be completely upfront about their unusual techniques. Corsair floats a basket of hops in the still to infuse their hop flavor, while Sons of Liberty and New Holland both dry hop the finished spirit. So it only makes sense that Charbay is also adding hops somewhere other than the mash to earn the label flavored. Exactly where it happens, they won’t say, but during a phone conversation with him, head distiller Marko Karakasevic did eventually relent and admit that there is more to the story than their simplified ad campaign leads you to believe and that the specifics are “none of your business”.

The inescapable truth is that heat is the enemy of hoppy flavor. When brewing beer, the earliest additions of hops quickly boil off into bitter vegetal notes. The later you add hops into the equation, the more bright hoppy flavor will end up in the brew, so many beer brewers choose to add their last dose of hops within the last ten minutes of the boil, or even afterward, to keep the flavors bright. Hop oils are some of the earliest things to boil off in a brew pot or still and most of it (not all) ends up in the discarded heads, so it’s no surprise why the hop flavored whisky distillers choose to adulterate the spirit inside the still, or later, with additional hops. The spirit needs help to really pack in that hoppy flavor. It is, coincidentally, also because of that volatility that you can use hops in a whisky mash and not call it hop flavored whisky.

There are uses for hops other than flavor. Hops are anti-microbial, and can help keep bad bacteria at bay while yeast takes hold in a substrate. Samuel M’Harry’s 1809 book, The Practical Distiller, talks about using hops to help propagate yeast. Bourbon-lord Chuck Cowdery offers some anecdotal evidence, as well. For a contemporary example, Maker’s Mark uses hops to keep their dona tanks clean today, while they build up the yeast before adding it to their mash. Technically, none of those are examples of hops directly in the mash though.

The efforts from George Washington’s resurrected Mount Vernon distillery and Ohio’s Indian Creek both bring hops a little closer to the mash. Both harness the antimicrobial power and make a hop tea. They use this tea as the mash water to help keep bad bacteria out of the mash. This was once a very common practice in whisky, though as other, cheaper sterilization methods surfaced, like steam, the practice of using hops to manage clean fermentation became less common.

So, if you use hops the same way distillers are allowed to use enzymes, to aid fermentation, the flavor is considered traditional and the addition of hops is considered irrelevant to the label. Passage 27 CFR 5.23 A(2) of the Federal Code states that any class of whisky (the one exception being straight whisky) may contain up to 2.5% harmless blending materials “which are customarily employed herein in accordance with established trade usage”. That means so long as you’re smart enough to provide the TTB with the historical precedent and the hops don’t drastically alter the flavor of the result in a wildly uncharacteristic way, it’s a perfectly legitimate adjunct. Although the paperwork and science paves the way for it, the three examples I’ve provided so far still aren’t putting hops directly in the mash bill.

photo from Albert Savarese

Enter 287, an American Pale Ale brewed by Captain Lawrence Brewing, distilled by Still the One and aged in virgin oak casks for about a year. This is a product that fits legally into the official American category malt whisky with no hop-flavored declaration despite the addition of hops directly in the mash. One small caveat, if any collectors out there can find this whisky now, grab it up. Future editions will not have hops in the mash bill. The distiller claims that the hops flavors all fall outside of the cut anyways, so to save money Captain Lawrence is no longer adding hops in future mashes… but they can and did and it did taste hoppy.

So why is this news? Well, part of it is the TTB’s code of silence. If you call an agent and ask them about the issue, not only are you dealing with a blank canvas and an individual interpretation of the Federal Code, but they won’t comment on any other distillery’s product or methods. Upfront, this seems like an honorable enough way to protect trade secrets. It limits information we receive as the public to what the distilleries are willing to divulge, but it also helps keep the history of distillation a secret to future generations and makes making a historical argument for your technique much harder. Distillery X might be making whisky with cat litter as an adjunct, making it a legitimate addition per 27 CFR 5.23 A(2) for other distilleries, but you would never know. If your TTB agent had never seen it before they might even prevent you from doing something which is already a common practice. The very laws meant to protect us and clearly identify the spirit in the bottle paradoxically provide a place for obscurity regarding its ingredients.

So from now on, should you ever find yourself reaching for that mantra to explain what whisky is, remember: whisky is just beer… distilled and then matured in an oak cask.

EDIT 11/23/13: One important thing I left out of the original post, but should have included, the bright hops oil may boil off in the heads, but there is a leftover bitter flavor that doesn’t boil off so quickly. According to the distillery, the bitterness that does not boil off in the heads is left in the tails, though, so it makes its escape by simply being left in the still with the feints. Also worth mentioning, though they claim the actual hops flavor may be cut out of the final product, the notion that hops are a totally irrelevant adjunct is incorrect. Even if you were to completely cut out every chemical trace from the hops, an impossible task, the use of hops still affects the flavor of the end result by affecting the fermentation.